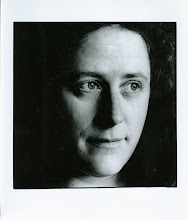

JACQUELINE RICHMAN SCHECTMAN

My mother, Jackie Schectman, who passed away two years ago, wrote this family history in 2002. She was spurred on by a slightly different version her sister (who died about 6 months after my mom) wrote. Below is my mother's preface to the Richman/Kanofsky family saga: "My sister feels this story should be told. She is no doubt correct, and with a long, slow summer before me, I’ve decided to take up the challenge. Will my telling please her? Who can say? I can only write what I recall so well from my own, personal, memories, and from the stories I was told by those who expected me to commit them to memory. Is it all true, in a factual sense? I cannot say, but if family mythology makes up a large part of one’s identity, something I’ve always maintained - this story is part of who I am."

HELEN KRIEGER REICHMAN GREENETZ

First, there was my grandmother Helen Krieger Richman Greenetz, the "shayna Helena, the toast of 19th century Poland." Standing barely five feet tall, she boasted that she’d never weighed less than 200 pounds and that her neighbors had always called her beautiful!" She was born circa 1870, the daughter of a successful businessman, the grandaughter of talmudic scholars.

She’d accompanied her arthritic mother to the spas of Europe, learning several languages along the way.(In her old age, she recalled only the profanities and a few odd phrases of these seldom practiced languages, and she was not shy about using her fund of international curses at appropriate moments. She was married young to a wealthy, elderly businessman, her beauty and intelligence making her a prize match for such a gentleman.

Predictably, the old man soon died, freeing his widow to marry again, this time to a traveling cloth merchant, Mordechai Riechman. There were family rumors of another wedding (and subsequent divorce) sometime before the marriage to Riechman, but no one knew any details of this. The third early marriage remains in the realm of family myth; how many husbands had Bubba outlive?

I do know that she had the words of the traditional wedding ceremony committed to memory. She’d been through the nuptial rites often enough.

While Riechman traveled, Helen tended her own family’s business, a substantial restaurant and tavern in Lodz, an industrialized, Germanic city in central Poland. I learned, later, that her family name "Krieger" could refer to either warriors or tavern keepers. While the latter was certainly, literally, appropriate, the former may have been equally descriptive of her personality. I have an image of her standing behind her tavern bar, carving knife in hand, fiercely slicing roasts and fowl. Occasionally, she might hand down a scrap to her youngest child - my father - who’d nestled himself below, in the bar’s inner recesses.

Such tastes of meat must have been truly welcome to the boy. He often recalled, with some bitterness, a war time diet of potato skin soup. Later in life, he considered a meatless meal both a painful reminder of these hard times, and an insult to his manhood. Words like "cholesterol" were not yet in our vocabulary, and my father thought of red, fatty meat as health food.

The war brought the family all sorts of grief. Helen had had ten children, and two sons had died as soldiers, fighting on opposing sides of the Great War. Jewish boys were simply swept up by any passing army, mindlessly drafted as human fodder by the combatents of the day. Three other children died young, and when my father, Michael, at 8 or nine, woke one day from his under-bar nap in great pain, they discovered he’d been stricken with Perthes Disease, a necrosis of the hip joint. His older sister carried him from doctor to doctor, but there was no help for him. He grew up with a short leg and more or less constant pain.

As an adult, he learned that surgery, followed by a year in traction, might still help, but he was a married man by then, and did not have the time or money to follow through with this treatment. He stacked the heel of his shoe on the short leg, and went on walking cutting room floors.

Aside from the loss and illnesses of her children, Helen had her own wartime woes. As the heavily disputed city fell under martial law, she was forbidden to sell alchohol to soldiers, a restriction that would cut deep into the tavern’s profits. No one could tell this warrior how to run her business, of course, and she proceded to sell drinks as usual, in defiance of the law. Soon, she was challenged at her bar by military police, and claiming that an obviously visible glass of vodka was only water, proceded to drink it down, neat. Unimpressed, the MPs took her off to a military prison, and she was scheduled to be hung the next day. Before the sentence could be carried out, however, the city changed hands, and the liberating army released all prisoners. She lived to tell the tale.

When the war was over, Riechman having died Helen felt it was time to leave for America, the "goldena Medina", the land of promise and opportunity in which her brother Israel had a firm foothold. In 1921 he sponsored a passage to Philadelphia for her and her four remaining, unmarried children. Married son Joseph stayed behind to mind the store, so to speak.

His death, in the Holocaust, is a sad and telling piece of family lore. In the thirties, as tales of Hitler’s excesses filtered through, Helen and the American siblings decided to bring Joseph out of Europe. According to my mother, however, they argued so long among themselves about their respective shares of his passage that the cash and papers arrived in Poland too late. He missed the last ship out and was lost. His son, who escaped in one of those miraculous tales of chance, daring and deception, remembers things differently. His father could have left, he told me, the money had arrived in time, but he stubbornly held onto the restaurant, waiting for a good price for the business. He refused to leave, and then it was too late. Both versions speak volumes about The Holocaust, not about the six million, but about individual hopes, miscalculations and regrets.

Cousin Michael

As my cousin and I exchanged stories in my Jerusalem hotel room we hung our heads in mourning and bewilderment. How could this have happened? Finally, we had to shrug, and move onto our plans for the evening.

The family’s journey to Philadelphia was neither easy nor uneventful, and whenever I’ve had to travel or move house with my children,I thought of Helen, in middle age, leaving for another, entirely unknown world with a crew of unruly adolescents. The thought has always filled me with awe, and shored up my flagging courage. If she could make this journey, thus assuring my existence, I could surely move my kids from Allentown to Worcester.

At the European departure site, 14 year old Michael lost sight of his family and was separated from them. Far from panicking, he simply boarded a larger, faster liner loading nearby, and arrived here some time before the rest. His greeting to his mother, sisters and brother, a family who’d imagined they’d lost him forever, was to ask what had taken them so long.

Upon arrival, all went to work for Uncle Israel in his embroidery shop. Florence and Bernie were to labor in the shop for the rest of their

working lives (Bernie would ultimately inherit the business, becoming a capitalist in an ironic finish to his Worker’s Circle, union-steward life.) Oldest sister Rose worked there as well, until she had two children, and died delivering a third. Michael (he would change his name to Martin, lest he be called Mickey, and be mistaken for Irish!!) worked there after school, but showed little inclination to take orders from his uncle. He was overcome by envy of his cousins, Israel’s children, who, encouraged to finish high school and college, eventually became physicians.

Helen and Israel circa 195o

Martin’s formal education was stopped at eighth grade, a never-ending source of bitterness to him. He did eventually go to a union sponsored trade school, learning pattern-making and cloth cutting.

He pursued the latter, as it was the highest paying position in the garment workers’ hierarchy, but this highly skilled intensly physical labor involved miles of walking pushing heavy, finely calibrated machinery through thick layers of cloth. Despite what must have been constant pain, he cut dresses, blouses and skirts for 40 years, until a coronary forced his retirement a few years before his death.

His fervent dreams of higher education were transferred to his daughters, and I was never unaware of this burden I carried on his behalf. In my drive to learn, I’ve always been acutely aware of his presense. When I walked down the long aisle of Philadelphia’s Convention Hall, to collect my Temple BA, in 1971, I saw him in the audience, standing on a chair, the better to wield his ever-present movie camera. I grimaced in annoyance, then turned to smile at the camera. At that moment, it occured to me that he’d been dead for five years! A brief hallucination, perhaps, but I’m still convinced of his spiritual presence in that hall. One of us, at least, had the prize in hand.

The family settled in Philadelphia, the older siblings attending night school to learn English, eventually meeting their spouses there. Helen learned the difficult new language from her children, as young people in school were instructed to speak nothing but English at home, and to insist their parents do the same. Helen later recalled, with a laugh, her initial confusion in asking the grocer for a pound of unions. She also remembered how much she’d paid for those "unions".

By 1928 the family had their citizenship papers, and made two discoveries: one, they could vote in the presidential election, and two, their votes were worth cash on the open market. Republicans bid high that year, and the family cast their first American ballots for Herbert Hoover. They came to regret this lapse so bitterly that they were fervent Democrats forever after. (My parents had a portrait of FDR over their bed, the family’s secular, patron saint!)

Bernie became an active organizer (FOR THE ILGWU) and the others followed suit. The Union was always a huge presence in our lives, providing assimilation skills, health care, weeks of summer vacations, college scholarships and my parent’s retirement pensions. When my parents spoke of the President, they were generally referring not to Truman, and certainly not to Eisenhower, but to David Dubinsky, head of the ILGWU. Another Lodzer, he was The Man.

While Rose, Bernie and Florence married and began raising families, young Martin pursued his new, very American passions for organized sport. He particularly loved basketball, worshipping the tall, agile players as only a short (5’2"), lame man might. Years before professional leagues, the Jewish Ys sponsored endless tournaments, Sunday night games followed by dances on the polished wooden court. It was at one such game that my father met the tiny, shy girl, Rebecca Kanofsky whom he would ultimately marry.

JACOB AND LENA KANOFSKY

My grandfather Jacob was a tailor in the Czar’s army, which is to say, he was drafted. My mother would later dramatize the tale into a romance, picturing her father astride a fine calvery stallion, but the truth lay in the small factory in which he turned out uniform trousers for the troops. She described him as tall (perhaps 5’4") and handsome in his uniform, irresistible to my grandmother, Lena Bressler. They married, and settled in the city of Ekaterinaslav, in the southern Ukraine.

Post-revolution, The city was renamed, at least once. Jacob, too, had to be renamed, as Lena’s father was also a Jacob. The coincidence of names implied symbolic incest and made the proposed wedding decidedly un-kosher. Jacob became Noah, for the sake of a good marriage, and retained the name, if only when addressed by his wife. Their first born, a son was followed quickly by Rebecca, in 1910. Jacob had served his time with the army by then, but the European peace was fragile, and a forced re-enlistment could happen at any moment. The couple settled down, waiting for the next boot to drop.

Relief came in the form of an unexpected gift. Lena’s sister was engaged to an adventurous sort, a man who’d saved and planned for immigration to America. Their papers and passage were in hand, officials properly bribed when the young bride found she could not, would not leave her family. There was nothing to do but sell all of it to brother-in-law Jacob. The young Kanofskys left Russia weeks ahead of the Revolution and the Great War.

Landing in South Philadelphia, Jacob opened a tailor shop, and

little Philip and Rebecca went to American schools. Joseph, Sarah and Ben were born in quick succession, citizens from the first. Lena, neither as quick nor as flexible as the older more sophistacated Helen, and burdened with five small children, made a difficult adjustment to her new home. When her children came home from school, insisting upon English, she responded with bewilderment and anger. Then she fell.

According to my mother, the fall was down a steep flight of stone steps, Lena went down head first, and fractured her skull. She was never properly treated, and was never the same thereafter, memory and cognitive abilities having been permanently damaged. My mother, at seven, was now by default, the housewife-caretaker for the brood. There were no grandparents or extended family to lend assistance, and the six were on their own, to do the best they could. Rebecca, called Bea, would have to depend on what she’d learned from her mother before that defining fall.

After her marriage, when Helen tried to teach her a thing or three about housekeeping and kitchen skills, she responded with stubborn resistence, thus launching a thirty-years war between the two. My grandmother’s weapons were shame and intimidation, battles in which everyone lost. I vividly recall my 80 year old grandmother hanging out our second-storey windows, washing their outer panes. The neighbors were horrified, and gave my mother considerable grief over this apparent abuse of the old woman. They’d never know that the window-washing was done entirely on Helen’s initiative, to teach my mother to "do it right".

But this would be years in the future. Jacob kept his tailor shop going with fine ladies’ work, but his gambling and more than occasional drunkeness hardly provided family security. Oldest son Philip contributed as a Western Union operator, and Bea was asked to leave school after 8th grade, to help support the family. This would prove to be a problem. While she’d sat at her father’s knee for many years, she’d never learned to sew, neurological problems having affected her eye-hand coordination. Unable to do, she could only recognize the errors of others, and work as a spotter, checking over the final product of the factory or knitting mill. There were few such positions available, but she did manage to stay marginally employed - until the depression made itself felt in the garment industry.

Thus, when Martin and Bea met in 1930, they required a long engagement to put aside even a minimal nest-egg. They also had to face opposition to the marriage from both sides. Jacob and his sons saw past Martin’s good looks and surface charm to his unbridled anger and bitterness, likely to erupt at the slightest provocation. They heard him order Bea around, and feared for her safety. Seeing what she wished to see in him, she defied them. Later, when she realized the wisdom of their advice, she could not admit her error and ask for help. She had no place to run.

Few women, I suspect, would have been good enough daughters-in-law for Helen, and she had little tolerence for Bea’s large and small weaknesses. Nonetheless, her youngest child was no more ready to bend to his mothers’ will than his mother would have been. The wedding was planned for November, 1933. (My mother, in fact, proved to be among the stronger of the Richman mates. Florence’s husband, Harry, suicided; Bernie’s wife, Tyana, spent most of their marriage confined in a series of mental institutions. Rose’s husband remarried shortly after her early death.)

Martin’s beloved older sister, poorly treated for a miscarriage in a public hospital died six weeks before the wedding. This placed a pall on the celebrations; music and dancing were cancelled, and the entire Richman family arrived for the nuptials in mourning clothes. The bride and groom, each barely over five feet and looking like wedding cake miniatures in their posed photo, were off to a most inaspicious start.

MARTIN AND REBECCA RICHMAN

Both worked hard, and Bea longed for a child and motherhood. Martin, remembering his sister, hesitated, but finally agreed to a one child family. Their little girl was named for Rose and Bea’s Aunt Ida, the names elided into Rosadele. Dark and pretty, she was the light of her father’s eye, a child who could do no wrong. As she grew, she became more and more difficult for her mother to handle, reporting her mother’s attempts at disipline to her father when he came home at night. Martin punished Bea, thus undoing any corrections she’d made.

Marty and Rose

Bea, caught between her child, on the one hand, and her mother-in-law on the other, felt completely outnumbered in her struggle with her violent husband. Hoping to improve the odds, she campaigned for a second child, promising her husband a son. Six years after Rosadele’s birth, she concieved again. It was 1942; this child would be a war baby. When Jacob died in a sudden heart siezure, she knew her son would be named for him.

I heard this story all through my childhood: When Dr. Arthur (Israel’s son) delivered me, and announced the birth of a girl, my father could not contain his rage. He hired a horse at a nearby stable, and rode the horse hard for several hours in an effort to calm himself. He blamed his wife, his cousin and anyone else he could find for his disappointment. A girl! He’d been promised a son! He needed to get away, he needed an object - Hitler would do - for his overwhelming anger. By 1943, Martin was 36 years old, lame and diabetic. He had two young children. Nonetheless, after a year of gathering false documents, he managed to enlist in the infantry. He was sent to Fort Gordon, Georgia for basic training. There, he would encounter the shadow side of the Land of Opportunity.

Shop windows near the base bore the legend :"No niggers, Jews or dogs allowed." Away from the cushioning familiarity of family, union and neighborhood, Martin was truly alone, with no outlets for his habitual explosions of rage. The disiplines of training had him in constant difficulty, and up to his elbows in potato peels, KP being a typical punishment for insubordination. Finally, his foot became infected during a long march, and he spent the next months in an army hospital, where doctors managed to save the foot. He returned home less than a year after his enlistment, frustrated in his desire to kill a nazi or two. Thence forward, his aggression would be primarily directed toward his family.

Jackie, Rose, Bea and Marty

The rest of the story?

Helen married for the third (or fourth ?) time to a man named Greenetz, and moved to Camden, New Jersey. After the war, she turned the large house into a boarding house for refugees. Her backyard garden kept her well supplied with fresh herbs and vegetables for her soups, while nearby streams provided fresh fish. Sadly, the easy-to-catch catfish were not kosher, and she had to throw them back, lifelong observance overcoming habitual thrift. Still, it was a good life for her, even after Greenetz died. She had a home. When Bernie defaulted on a loan on her property, she lost the Camden house and was left to wander from one relative to another, moving her pots, pans and kosher dishes with her.

Helen and Rose

Thus, by 1950, she was part of our household, adding another layer of richness and conflict to our far from peaceful home. The primary battle was over household management. Helen had been a professional cook; Bea did her best, but had little interest in the food she served. Her kitchen was neither organized nor clean, her meal choices based solely on her husbands demands. In the end, Helen gave up Bea as a hopeless cause, and looked around for someone else to take up the household responsibilities. My sister, for a number of reasons, was neither willing nor available, and I became my grandmother’s designated apprentice. When Helen took me in hand - I was perhaps nine - she declared that my education must include the making of a good chicken soup. Lacking such basic knowledge, she told me, I would never marry.

This messege was no doubt meant more for my mother than for me, but I took it very seriously, and learned. Another conflict arose around the issue of religion. Helen took her rituals and observances most seriously, weeping and praying over her tattered siddur morning and evening. Martin, on the other hand, would have none of it. His mother, he said, made up the rules as she went along, inventing more as she grew older. He declared all rabbis bloodsuckers, and refused to join any of several local congregations. My religious education was out of the question, but I was expected to escort Helen to the Orthodox shul on the high holidays. I soon learned to hate the chore. I had no understanding of what was happening there, and there was so much that frightened and mystified me. Why did they make my aged grandmother climb all those stairs to the balcony? Picking up cues from my mother ("We don’t have the money for new outfits to show off...") I thought the balcony was for those too poor for floor seats. It was years before I learned that Helen’s segregation was based solely on gender, not economics. The balcony was for women.

In any case, Helen’s trips to the shul became less frequent as the years went on. The young rabbis, she declared, just did not know what was what. She required no intermediary in her ongoing dialogue with her God. As her health became more precarious with age, she refused Friday night trips to a hospital with the following arguments: If she were to die on shabbos, it would be a mitzva. If God wanted her to live, she’d live until Sunday. She was to live a very long time. My father was not so fortunate. Weeks before his sixtieth birthday, he had arterial by-pass surgery, a procedure very new in 1967. It did not go well. In the weeks before his death - his doctors were optimistic - he asked to see a rabbi, shocking everyone who knew him. A rabbi was found for him, they talked, but none of us ever knew what they said to one another. We can only presume that his mother’s "nonsense" had some meaning for him in these last days of his life.

The third source of conflict was around conflict itself, that is, the response to my father’s violent temper. Helen urged compliance to his demands, however unreasonable, and left my mother with no support for her own needs, nor for ours. He was to be treated as the king of the household: he was to have the softest chair, the best food, the last word. For all her strength, he terrified her, and she passed her terror on to the rest of us.

Lena Kanofsky fared less well after Jacob’s death. Diabetes rendered her blind, and, in despair she attempted suicide. Her children, each struggling to raise families of their own, could not adequately care for the helpless woman. If there were institutions dedicated to care of the blind, the Kanofsky’s were not aware of them. She was consigned to Byberry State Mental Hospital, just northeast of Philadelphia, and died in one of its back wards sometime in the early fifties. I never met her.

.jpg)

.jpg)

.jpg)